You might remember me blogging about the Indianapolis incident where three babies died after being mistakenly given an adult dose of heparin back in 2007. The same set of failure modes led to a non-fatal overdose of actor Dennis Quaid's twin babies.

These episodes teach us a lot about failure modes in healthcare (it's often multiple things that go wrong in succession) and the management response to these problems.

It seems that hospital leaders often blame individuals for what appear to be systemic problems.

Some instances I've blogged about before:

- A Wisconsin nurse jailed for a medication error

- An Ohio pharmacist jailed for an error that occurred in his department

- A New York lab that fired “the technician responsible” for an error

I was at a hospital recently where we were talking about the Indianapolis case and I found an article that had a detail I didn't remember from that episode:

“Hospital Changes Procedures After Babies' Fatal Overdoses”

The article, included some early reporting onthe errors that killed the babies, including:

Early Saturday morning, a pharmacy technician with more than 25 years' experience accidentally took the wrong dosage — vials of 10,000 units of heparin — from inventory and stocked it in the drug cabinet in the newborn intensive care unit, Odle said. Five nurses, who are accustomed to only one dosage of heparin — 10 units — being available, then administered the wrong dose.

The adult and infant doses have similar packaging, officials have said.

Here is a picture of the similar labeling (a mistake waiting to happen) and a second picture showing an error proofed version:

You can see how an error might have occurred in a dark hospital room, early in the morning, with the first picture.

The article continues, in terms of responses:

Starting immediately, Odle said, all Clarian hospitals — which also include Indiana University and Riley Hospital for Children — will no longer keep vials of 10,000 units of heparin in inventory.

Also, all newborn and pediatric critical care units will require a minimum of two nurses to validate any dose of heparin, and two pharmacy workers will be required to check the drugs being loaded into the cabinet. And nursing units will receive an alert when a change in packaging or dose is entered in the drug cabinet.

That seems like a prudent step, not keeping an adult dose of a medication in a children's hospital.

I would generally worry more about the reliance on inspection as a quality control measure. When you have two people checking something, they might get lax and think “the other person will catch a problem.” Human inspection isn't 100% effective, even with two people involved… because we're, well, human and we're not perfect.

The thing that bothered me the most:

In addition, all employees will be required to sign a document about the importance of correct drug administration by Sept. 23.

Sign a document? That seems like a piece of “patient safety theatre” (along the lines of what some call “security theatre” at the airport).

Having employees sign a document seems to be a very weak form of error proofing. I'd assume that people already KNEW that it's important to give the proper dose of a medication. People KNOW they shouldn't make mistakes. But that awareness doesn't prevent errors when there's a bad system.

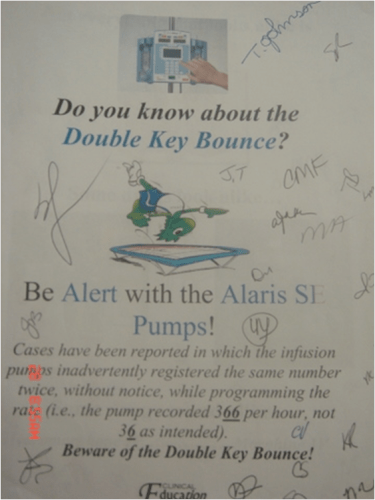

I saw another example at a hospital where nurses where told to sign a poster that highlighted systemic design problems with a brand of infusion pumps often referred to as “the double key bounce.” The sign warned about not punching in the wrong rate (such as hitting 55 instead of 5) and the signature seemed to imply a promise that's impossible to keep.

Here's what we're often expected to promise:

- Promise not to be human.

- Promise not to make mistakes.

- Promise not to be defeated by a device with buttons that sometimes register twice for one push.

We need to do better. How has your hospital progressed in terms of thinking about systems instead of blame since 2007? Has Lean helped in this shift toward proactive prevention of problems?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Brilliant. You know I think maybe I was wrong about thinking that just deciding not to make errors was not a great strategy. After so many others seem to think that is the best method maybe I should reconsider my thoughts that changing the system (poka yoke and the rest) is what is needed.

Hmm.

Actually no, I think changing the system is actually the right answer. :-)

I wonder how well it would have gone over to ask surgeon to sign a form saying they would not perform wrong-site surgeries any more after having accidently done so? or, maybe the docs should include the phrase “… and please make sure you administer the correct dose” after each prescription… that would surely be helpful.

Whoops, my cynical side just came out.

Ron

I’ll add a note below the comments field here reminding people to not make any typos or misspellings. :-) Let’s all make a promise to that effect. How does that ensure quality?

“In addition, all employees will be required to sign a document about the importance of correct drug administration by Sept. 23.” … This is the ULTIMATE in ineffective command and control blame & shame thinking without even a thought to PDCA… Not to mention disrespect.

At what point do the episodes of jailing people for being human become a deterrent to people considering healthcare professions?

Mark W – well said. That’s why the idea of signing a form was appalling to me. It does nothing to improve quality and it probably active discourages people. Jailing people for systemic errors is absolutely ridiculous including for the reason you cited.

Part of the problem with blaming and firing and jailing is that it “sounds good” unfortunately to the general public who buys that as a response to these incidents.

Signing a document? Sheesh. Don’t they know placing big posters everywhere reminding people to not make errors is more effective? ha ha ha

Signing a document that they won’t make a mistake?? This is more evidence of the primitive nature of nursing leadership’s approach to quality assurance. I think we need a shake-up in nursing leadership training.

Agreed, anonymous.

To share a bit of sunshine through this gloom, I spent the last two days at ThedaCare in Wisconsin. I heard their CEO and a front-line nursing manager both talk about the new lean culture:

– Moving from blaming to focusing on processes and systems

– Not being punitive but instead being a coach and leader

– Get everyone involved in process improvement

It’s very impressive to see how that mindset has become ingrained deeply in the every day mindset of leaders there.

When I studied epidemiology at University, they talked about a parallel issue – statisticians giving evidence in smoking cases. No health statistician or epidemiologist would give evidence defending smoking because they couldn’t (they would be lying) and it was unethical to do so.

However, Big Tobacco founded non-health statisticians to put their case. These people had the role of ‘muddying the waters’ and bamboozling the jury with stats rubbish to make them think clear causation was not so.

I’m thinking it might be time for Lean and other quality people to intervene, Amicus Curiae, in cases of people being thrown in jail over quality issues. In effect, we should be saying it is not enough to show a single, linear, causation equals criminal culpability. To me, culpability would be trying to actively defeat safety or other systems, not merely acting them when the system is broken.

Apart from the damage it does to improvement efforts, to me it just isn’t causation and fails a legal test of proximity.

It would be no different from say an aircraft refueller not putting enough fuel in the aircraft. Throw him in jail, or ask: How could a plane take off without enough fuel for the journey. What safety systems prevent this? What electronics or mechanical devices prevent this? What distracts a refueller doing his job? And so on.

Brilliant and well said, Richard. How do we make that vision a reality, convincing society that naming, blaming, and shaming doesn’t improve quality?

Mark;

You may have inspired California to get tough on these errors.

http://lat.ms/cR7uE4

Notice how many of the hospital responses say they will retrain people? That sounds like blaming to me.

In the cases where “standardized work” (if you will) wasn’t being followed, where is management to help manage that BEFORE an incident occurred?

I was in SF over the weekend and saw a news report that included hospitals that had been fined (like UCSF). I then, 30 minutes later, saw a TV commercial for UCSF that was bragging about how they had “the best doctors.”

That might be true, but “best doctors” along with sometimes (and allegedly) sloppy process isn’t going to lead to the best healthcare quality or patient safety.

But “best doctors” sounds good to the general public, eh?

The best doctors are the ones who, in additioning to their experience and training, are carrying out standard work for their common cases with minimal waste – leaving them enough time and brain space to work out what to do in the rare cases.

Doctors having to walk miles on a round, having to spend hours by the bed but then more hours writing reports and notes, having to fill in forms for administration, having to ask for things and ask again, getting so tired they make mistakes (which, besides the impact on patient, is also just rework).

If I want a well-trained doctor working beside my bed or a surgeon operating, we need to cut as much of the waste out of the system as we can to free them for that time. They go to Medical school to learn Medicine, not how to fill in forms or how to walk down a hospital corridor. That is my value proposition for wanting a doctor.

Honestly, if I am allowed to blame anyone, why can’t I blame hospital architects. I’ve worked in a few in my life and can’t understand why they are not designed as an in-and-out arrangement based on patient flow.

Walk-in Emergency cases should be able to do everything they need within 100 feet of the hospital door, and the doctors and nurses who care for them also should never need to go that far.

Those cases that are likely to require admission, diagnostics, operating, recovery, on the ward and discharge, should be done in as short and straight a line as possible.

And classic departments like pharmaceuticals or central sterilising facilities that no longer need to be central, should be broken up and placed at the clinical unit level or even at the bed, with only highly unusual or dangerous materials or equipment kept centrally.

While there have been studies showing the signing of these type of documents can change behaviors in the moment, they have also shown they have no long term effect. Obviously asking staff to sign something like this before every shift would not be possible. I do however like the posters. Not because they will make changes in the moment, but they show the staff support and the importance of the issue. It inspires a feeling of teamwork to combat the issue.

You hit the nail on the head that these measures are not effective in the longterm. I’m less concerned about “feelings” of involvement and more concerned about quality and patient safety results. I think the longer-term harm from signs and posters is that it teaches sloppy, lazy, or ineffective problem solving methods. I’ve seen too many hospitals where the solution to everything is hanging up another sign or warning or reminder.