Last week, I published Part 1 of my notes about a breakfast talk by Dr. Brent James at the Shingo Prize Conference.

One of the more interesting things that Dr. James said was something he prefaced as saying it would be a criticism of Lean. Dr. James seems generally very supportive of Lean and TPS as a helpful force in healthcare, but he has reasonable criticisms — criticisms not of “lean” itself but of “lean as commonly practiced in this country,” as he put it.

In Dr. James' view, Lean has three pillars:

- Flow & standardized work

- 100% participation

- Mass customization

James' criticism is when only the first pillar is emphasized. Focusing on flow with out staff engagement and flexibility does sound more like “L.A.M.E.” (Lean as Misguidedly Executed) than real Lean.

For what it's worth, I encouraged Dr. James to repeat that criticism as loudly and as often as he could, since it's not a criticism of what you might call “true Lean” — it's a criticism of how it's often practiced. “Fake lean” or “L.A.M.E.” (or whatever awkward term you give it) helps nobody and it gets in the way (due to bad reputation) of those trying to practice Lean the “right” way.

I'd actually create two different “3-legged stools.” One would have Lean healthcare focused on:

- Quality / Safety

- Flow / Access

- Cost (for patients, payers, and providers)

And benefits would go to to a balance of:

- Patients

- Providers

- Healthcare Organizations

Whether using my constructs or Dr. James', I'm in full agreement that focusing only on flow or only on efficiency is not Lean. I've complained before when some people say that Lean is about flow and Six Sigma is about quality. No. The Toyota Production System has always been built on flow/just-in-time AND quality at the source.

There's no denying that Lean is about both flow and quality. Or it should be, unless you misunderstand it or have been taught badly.

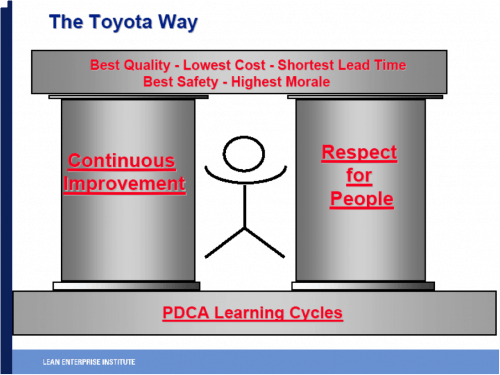

Dr. James is also correct to point out, basically, that we also need a balance between the two pillars of the Toyota Way — continuous improvement AND “respect for people,” as shown below.

Dr. James told a story of a major “Lean hospital” that had a number of doctors quit because they felt like “respect for people” was missing (my explanation of it). Dr. James told of doctors being followed around with stopwatches — that fell short of true 100% participation as he referred to it. The “efficiency experts” took away the doctors' chairs because they would be able to chart more efficiently without having to get up and down.

This was done TO them.

Argh.

Getting sidetracked again a bit from Dr. James' comments, there's a similar theme that I wrote about in a piece co-authored for the (I think) July/August Journal of Hospital Medicine. Edit — here is the piece.

There were two pieces written by people at academic medical centers describing their “Lean” process and elements of it sounded exactly like what Dr. James was warning against – they were ignoring respect for people. The one hospital wrote about, guess what, following hospitalists with stopwatches and even timing or making note of how long they were in the bathroom.

To that, I think, “Are you TRYING to make people mad???”

In the JHM piece, my co-author (from Northwestern Memorial Hospital) and I asked are you treating the hospitalists like “Subjects or Scientists“?? It's wrong to treat people like the subject in a science experiment, just following them and not engaging them in the process of identifying waste. That's very “Taylorist” to just follow others with a clipboard. That situation seemed very low on the respect for people scale. You need to treat everyone like a scientist, allowing them to participate fully in the PDCA cycle related to their own work.

Dr. James, again with his roots in working with Dr. Deming, talked also about how he has been through every possible improvement methodology that's been thrown at him, including

- Total Quality Management (TQM)

- Re-engineering

- Motorola-style Six Sigma (not meeting his 100% participation goal)

- Alcoa-style TPS (Toyota Production System)

- GE-style Six Sigma

- Now, a more Toyota-style Lean approach

As many complain about, Dr. James says that this new program mentality is often the fault of consultants repackaging things as something new to sell. In these different efforts, they:

Usually emphasized tools, and sometimes new tools, to roll out the new method.

The focus on tools is not a problem unique to Lean. Nor is it unique to try to “roll out” these methods in a very top-down command-and-control way (a way that usually does not show respect for people). Dr. James emphasized:

You can't manage doctors through command-and-control.

But, you really shouldn't manage anyone that way. Again, what Dr. James says he sees a lot of in “lean as commonly practiced today” is a bad Taylor-ist form, we can't take that approach (again, I'd call that L.A.M.E.)

Why do people, across industries, tend to fall into this Taylorist command-and-control approach? Dr. James said:

It's basic human nature… your God-like power to control others…

I've never heard it put that way…. it makes a lot of sense that people would be attracted by that sort of “power” over others. So when we ask why people won't give up that control to have a Lean culture, we're fighting human nature? You can, unfortunately, take any tools (Lean or Six Sigma) and throw them into a command-and-control culture.

And you're likely to not get real sustainable results for the long-term. Dr. Stephen Covey has been saying the same things about how command-and-control is the wrong approach.

Dr. Deming was teaching that decades ago, why aren't people listening??

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

Join me for a Lean Healthcare Accelerator Trip to Japan! Learn More

Perfect. Love this set of comments. Do you suppose, if we repeat things like this enough times, that people will understand that it’s not about the tools, it’s about building a culture? It’s not about flow, it’s about involvement? It’s not about stopwatches, it’s about helping people solve their own problems? Great stuff.

I think the urge to fall back on command & control often grows out of the frustration of getting others to see things our way and trying a change. For every command & control Taylorist, there’s at least one recalcitrant, “no way am I going to change the way I’ve been doing things for 27 years” doctor (or nurse or engineer or customer service rep).

If nothing else, I think that the Taylorist default setting is due less to a desire for God-like powers, and more to our experience as parents (and children): when a 2-year old doesn’t want to take a bath or eat his brussel sprouts, the parent simply says he has to — end of discussion. That mode of operation is ingrained in all of us.

First of all I agree with the good doctor, there is way to much emphasis on tools of all sorts. The most under discussed point of the TPS system is the human relationship that spreads through it and for that matter any great enterprise. Any truly great enterprise has a common factor of respect for people, coming first. It always starts with owners that show respect to both those they employee and those who buy their products. Surprisingly to some the companies with the most loyal and fair ownership also have the most loyal customers. Loyal owners treat workers with respect, they do not ask workers to suffer for them rather they take it on the chin first. Organizations built on mutual respect than naturally respect their customers, who in turn repsect them. It oftens has little to do with quality, but much more to do with personal treatment that build loyal customers.

Healthcare like the auto-industry keeps trying to solve their problems by imposing some new system on the workforce that does the actual work, instead of first seeing what owners and execuctives can do to straighten their house first. This causes resentment, as the wokers see the others still getting the gold plated treatment while they are constantly asked to give up more.

Anyone that implies doctors, and for that matter any health professional, does not accept change easily is blind. Their profession demands they adapt to more change per year than most of us face in a decade. What they resent is outsiders to the whole healthcare practise, telling them how to do their jobs, instead of asking them how we could help them do their job better. These people juggle the demands of having to ensure they run enough tests to not only know how to treat people, but to also prevent legal actins, while being told they need to cut costs. To often we demand opposing actions.

Next medical staff are asked to be able to instantly shift gears between a patient who has medical insurance that requires added services to providing service to someone without any insurance. How do you balance all the different requiremnts they are faced with. Add to this they have to answer to admin, accounting, finance, legal, and medical superiors, now you add a group of supposed efficiency and quality experts, none of whom know anything about medicine, how would you feel?

I have seen hospitals were people pulled together and achieved great things despite the differences, but they began with the top showing respect for everyone under them, and a wellingness to put everything on the table to see how things can be made better. Consultants, and hired guns (expert managers) are often under pressure to show instant results, so they try attacking symptoms instead of the real problems. You start by learning about the people, than you start seeing who can help fix what. After all the only really good solution is the one they come up with anyway.

If everyone (all of our society) in the equation pulls together we can solve healthcare, but if everyone keeps trying to go it alone, we will continue to lose control till healthcare collapses.

Excellent discussion. Dean, I especially like your succinct dualisms.

The work we do starts with people, it is about people, and it’s principal benefits are for people. That means our work (our calling?) is enmeshed in the fabric of human nature–both the uplifting and the unsavory portions. We’re not going to change human nature. A focus on the uplifting parts will more surely lead us toward the lean ideal.

Dale

I’m wondering if Dr. James’ story of the “lean’ hospital where physicians lost their chairs and were followed around with stop watch efficiency experts is a fictitious account of how lean might go wrong. I think if such a place existed (in this country) many would know about it.

I think his point is that physicians, at leaset in the current enivronment, should not have to subordinate to a management system

Dr James said it was a real story and even cited which specific hospital it supposedly happened in.

[…] embargo, tal como bien señala Mark Graban en su Blog, en relación a Lean Healthcare, hay muchas empresas y organizaciones en que se implementa la […]

As in so many things, the truth likely lies somewhere between the extremes. Often balance is the best approach. Thus, there may have been more involved here than the good doctor implies or gives credit. I can recall being in a Toyota affiliate’s plant in Japan where supervisor’s desks and chairs had been removed from offices and replaced with stand-up desks in the middle of the individual’s department … to much initial grumbling and belief it was a draconian step, I was told. But, in pursuit of having their leaders on the production floor a greater amount of time and focusing on working with associates and their teams a greater portion of the day to make products easier and better and safer, the plant wanted to de-emphasize leaders doing paperwork and being tied to their desks versus doing more coaching, having more involvement with teams and the process. Being out there and moving about also meant being more informed and ready to help solve problems and also proved more healthy. Nothing sent the message better than getting rid of the chairs and desks and bringing the leaders to an equality with their teams, the plant improvement team said. As a patient I would prefer more time with a doctor versus having him-her locked to a desk doing paperwork, a poor use of his-her talents and time. So good-bye to the dratted chairs — I am all for working upright. And having folks (albeit themselves or other members of a team) take a more methodical approach to analysis of how time is spent is not all bad, when one thinks about it. So let’s not automatically decry timing as part of probing process improvement. Most of us are always surprised at how much time we spend on certain activities that keep us from the real organizational purpose (studies show we under-estime our own waste) — and being able to document our existing process accurately, versus just conjecture about it, is again a real help at making improvement. Information and metrics are great when you have an objective to make things better. We can paint that as some rigid, unthinking, inhuman approach by an “efficiency expert” or merely a step to give our teams more and better information on the current process so we can improve it to put more focus on the customer, in this setting the patient. Recently after a physical I sat with my doctor, the head of a local facility in a major hospital system in Greater Boston, who was doing data entry as part of a new medical info system. I could have done the data entry myself or even marked a computer-readable sheet with my answers versus giving him the answers to enter or done this with a non-medical person — versus taking 20 minutes with the doctor. He could have spent the time instead on quality interaction with his patient. He told me an internal hospital team, including some on his own staff, had decided on this approach, and as I pointed out possible alternatives, he agreed there were in hindsight better ways than they the route they had taken. It had added two hours to his day and would last almost a year he said, as many patients were seen only annually. Employees should and must be deeply involved with process improvement but often an independent, objective outsider can be part of that team and facilitate better results by the whole team. In short, I don’t automatically assume that what the good doctor cited as totally negative necessarily had to be or was. In a different context these may well have been very positive and a help to achieve the real goals of better, higher quality patient care.

LJ

[…] unlike Dr. Brent James, Seddon can’t separate “lean done wrong” with “Lean” in general. […]

[…] things have happened in manufacturing companies, accounting firms, and sometimes hospitals. It’s unfortunate when these things happen and it reflects badly on those leaders and […]

CAN YOU ADD ME TO YOUR LIST?

tHX

[…] Info de Toyota automotriz. Imagen LeanBlog.org […]

Mark, as I revisit this post I think some excellent points were made by Dr. James and you.

There is a balance between standardization and flexibility that can turn a lot of people off if standardization is applied wrongly. I know Seattle Children’s frequently uses the term, “reliable method”, instead of standard. I actually think this is a better term.

I attended an SAE (society of automotive engineers) conference in the late 90’s where there was an adhoc presentation from an engineer from a local Toyota plant (So Cal truck plant?) and he said that the Toyota Production system had four elements:

Respect for humanity (customers, employers, suppliers)

Quality at the source

Relentless elimination of waste

Strength through flexibility

Consistent with Dr. James’ comments, we (most) ignore the respect and flexibility points too often in our pursuit of Lean. Dr. James’ has over 20 years success not ignoring these two often overlooked points.

Comments are closed.