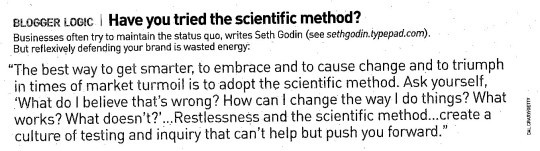

This was in Inc. magazine, a quote from a favorite of mine, Seth Godin (click on the graphic for a larger, easier to read view):

The scientific method is the basis of PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act), also known as the Deming Cycle (or the Shewhart Cycle). It's also known as PDCA (Plan-Do-Study-Act). It's also been re-named IDEA (Investigate, Design, Experiment, Adjust) by the design group IDEO… but I digress.

What do you think of the quote? If Lean and TPS is all about a scientific approach to problem solving, how much do you see that actually practiced in your own organization?

When you put a change in place, do you have a hypothesis about what you expect to happen? Do you disprove (or prove) the hypothesis based on observation and data?

PDCA / PDSA is intuitive to most people in healthcare… they were taught the approach (and they've often heard of Deming), but is it really practiced? Do you have a “culture of testing and inquiry,” regardless of your industry? Is that something you aspire to?

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety—together. If you're a leader aiming for lasting change (not just more projects), I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s talk.

"testing and inquiry" – great words that capture the spirit of PDCA. I think more and more people seem to get, at least intellectually, the spirit of "testing and inquiry" and PDCA. Where they struggle is the application?

A lot of people have started trying to replace PDCA. I don't think that is productive. There is LAMDA for product development and IDEA which is a convenient acronym I expect designed more for marketing purposes. Instead, teach people that PDCA is the core and give them / develop new tools that help them apply it. After Action Reviews, A3s, and so on – all tools and methods that help you apply PDCA. It's the application where people struggle.

Thanks for sharing the quote. Seth Godin appears repeatedly to be a "lean thinker."

Jamie Flinchbaugh

Mark:

We're back to standards and standard work aren't we – a culture with PDCA at the center is not just about projects or special investigations, but work that is designed so that every cycle makes problems apparent and thus creates the opportunity for continuous improvement. When these concepts start to click, when one begins to understand the relationship between standard work and kaizen, we begin to see the potential in this thing called "lean."

So, to your question, I don't think that intuition about the scientific method is enough. Scientists can compartmentalize as well as anyone and may apply the scientific method to their research questions but totally ignore it in their research work. And while the practice of medicine looks alot like science to outsiders, it's generally a couple of steps removed.

I appreciate the different acronyms because they refect differing perspectives (I'm enjoying Tim Brown's book!) on the improvement cycle that can deepen our understanding, but I'll admit to being happy with plain old "PDCA." Just trying to make it real!

-ALB

Since I started with Deming and then came to understand Lean, I have a special affinity for PDCA. I think it boils down to theory->test->results->proof/learn. I've recently taken the PDCA model to explain how to develop "good" metrics. I think we tend to create metrics simply to measure what we can or what we think we should because everyone else does. If you follow the PDCA model, metrics are the "C" stage, and starting at check would be just silly, wouldn't it? I suggest that every metric should be the measure of the test of a theory. Start with the theory, develop a test, measure the result and see if you have a valid theory or not. Measuring Cost, Quality, Safety, Delivery and Morale without specific theory or test seems pretty silly when you use the PDCA model as a guide. Like you said, it's hard to find anyone that finds fault with PDCA, but I think people lack the ability to readily see how it ties to what they do; make that tie, and you'll begin to see it used.

Seth brings some great stuff to the table, and I link him a lot, despite never having set foot in marketing.

Another under-rated thinker in my opinion is Scott Adams. (Yes, the Dilbert author.) His blog has very intriguing questions and observations regularly. In fact, in yesterday's post (http://dilbert.com/blog/entry/decisions_with_incomplete_knowledge/) he listed out a series of questions for decision making. Worth a read, to be sure.

Andrew, I really like your insight–the real value comes not with intution about PDCA but through internalizing PDCA. Of course, that takes time and a lot of learning. In the early going, people are still apt to jump to solutions. Building the discipline to frame proposed actions as experiments is helpful. Metrics are key in both the set up and the assessment.

Regarding names and acronyms: it seems to be a natural (consultant-driven?) phenomenon that good ideas are retread with a new name every so often. Sometimes they catch new life and find a new audience–I kind of like IDEA. The risk is always that the original, core principles are diluted or deformed.

Dale Hershfield

Good topic, we struggle a lot to get the improvement teams to complete the cycles. They just love the action part.

Recently an article came out in Quality and Safety in Healthcare about the origins of the scientific method, both in industry and in healthcare, and it also discusses how it relates to continuous improvement. A quote (describing the beginning of the 20th century):

"The scientific management expert owned the process. For quality improvement, the workers own the process and the quality improvement expert acts as a coach and helper. Team work becomes central."

http://qshc.bmj.com/content/18/5/413.full

Marc Rouppe van der Voort

Thanks for the link, Marc. I'm going to buy that for $20 and I'll probably blog about the article (although I won't be able to post it for everyone).

I would also submit that if you are working in organizations paralyzed by analysis … you can alter the sequence to Do/Check/Plan/Act for the simple reason that you can't really learn unless you are in action.

"You can't learn the game until you play the game" … just like the last time we all learned to play a new card game.

The key is for leadership to create an environment where experimentation and "curious action" is supported … even if your hypothesis going in turns out to be incorrect.

My two cents,

Dike

Dike Drummond

http://www.superteams.com