Today it's Toyota, tomorrow the NHS; Hospital looks to adopt safety initiative

The concept of any worker being able to stop the line in a Toyota plant is a key part of the quality strategy.

In traditional manufacturing settings, management will pressure workers to keep the line running at all costs — quantity over quality. If defects are being made, keep the line running and you'll sort them out at the end of the line (through inspection and repair). It's a failed quality strategy because it ultimately costs more and potentially leads to more customer dissatisfaction than if you had just stopped the line to immediately fix the problem and prevent more defects from being made.

In a Toyota plant, this is called an “andon cord”, a line that the worker can grab to notify the team leader (supervisor) that there is a problem. This could be a quality defect or any problem (such as dropping a bolt). If the supervisor can't help resolve the problem in the job cycle, the line stops (often, pulling the cord does not really lead to a line stoppage because the problem is fixed immediately).

It's great to see that hospitals are starting to adopt this quality philosophy — empowering healthcare workers to “stop the line” or stop the process to make sure an error is not going to occur. For example, if a tech in the operating room suspects that the wrong patient has been brought in, they can call a time out and raise the issue.

In the article linked to at the top of the post, some hospitals in the UK are using this “stop the line” strategy:

Although planning is in the very early stages, it is thought a check-list for procedures would be highlighted and an employee who believed routine was not being adhered to could page a senior member of staff to call for immediate assistance.

Gateshead Queen Elizabeth hospital's medical director and surgeon, Bill Cunliffe said: “We want to empower all members of staff and we place a strong emphasis on patient safety.

“Junior members of staff can lack confidence in approaching senior members if they see or feel a medical procedure is not being done right.

“‘Stop the Line' would empower all staff to take action and literally stop a procedure in its tracks in order to prevent a mistake being made.”

This isn't just similar thinking, it is inspired directly by a visit to Toyota in Japan:

The idea for the process came when health officials sent a delegation to Japan last year to discover ways of increasing efficiency in the health service.

The group, made up of senior doctors and chief executives, visited Toyota to see the management systems that have made it the world's biggest carmaker.

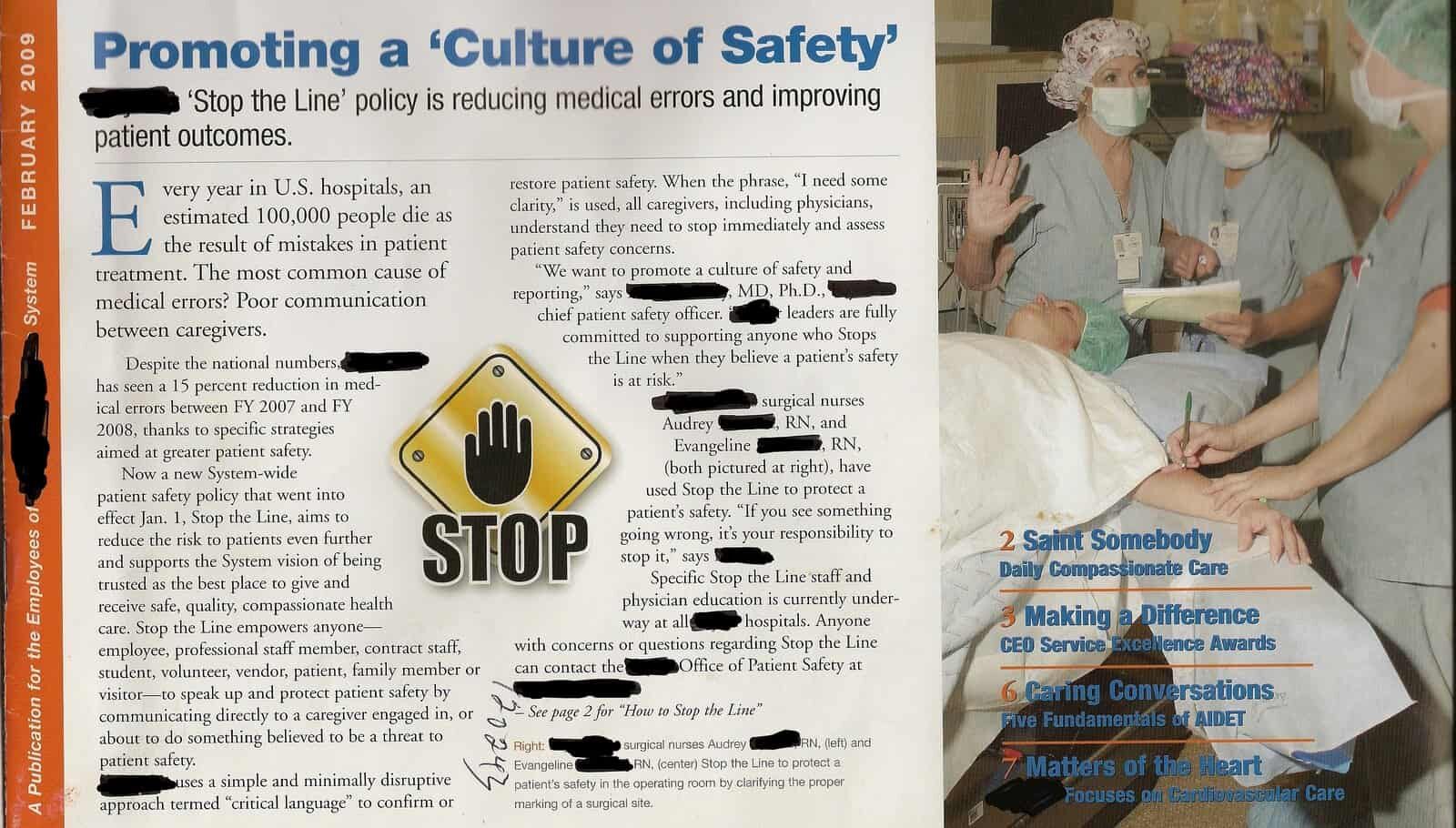

The picture below shows a similar document from a U.S. hospital. This was in an employee newsletter, so I'm assuming it's not public. The hospital deserves credit — I'm not blacking out names to protect the guilty, by any means. Click on the photo for a larger view and this hospital's use of the approach.

Staff members are taught to stop and ask, “I need some clarity…” Stop and ask immediately. I'd be curious to see what action hospital administrators would take if someone tries this and isn't listened to. What's the immediate escalation process if a surgeon refuses to stop or acknowledge the stop the line request? The article says the leaders are fully committed…. I hope so.

This is far superior to another hospital I visited in late 2007 that had an “andon” type process. The thing I didn't like about that process was that it wasn't real time. Employees could send an email or call a voice mail line AFTER the procedure. That's too late. That's not stopping the line. I like the approach shown in the picture that teaches people to stop NOW and ask questions NOW. Even if you're wrong in the question (thinking there was an error when there was no error), that slight delay in the name of safety has got to be better than being quiet when you think something is going wrong.

What's your hospital doing in this regard?

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

Hi Mark,

This happened just last night on ER. All of the old cast was back, which probably raked in the highest ratings for the show in years. Anyway, Dr. Benton observed Dr. Carter’s kidney transplant. The surgeon was late, arrogant, short on time and didn’t like people watching over him. Dr. Benton, stood his ground and asked to cover the pre-op checklist, much to the ridicule of the surgeon.

It’s a good thing he did, later in the show, the kidney had to be removed and treated in a solution that was found to be absent in the operating room only by running through the checklist. Dr. Benton used that as a teaching moment to ask a nurse, how long would it would have taken to get the solution if it wasn’t in the room? 15 minutes. How long could the kidney last without the solution? 3 minutes. Carter lives! Three cheers for Dr. Benton!

As I watched the show, I couldn’t help but think that this was a message for all of us – we can throw all the government money at healthcare that we want. But the QUALITY of healthcare often comes down to human nature and our willingness to do the right things. Doctors are people too, they get impatient, have bad days and forget things – just like the rest of us.

Another point, this was a problem that government regulated healthcare won’t catch. This, like the millions of problems people face everyday can ONLY be found in the genba.

Even if the government imposed checklists, we know people won’t use them because of resistance and resentment. Therefore, the only thing that is going to improve healthcare are the people working in the industry. The systems they create are constant reminders, encouraging them to do the right things when we face adversity in it infinite forms.

I know you have praised the merits of checklists in the past as a form of healthcare standard work and hope we get to see a lot more of that as people improve their systems.

Not a good idea to use a scientifically inaccurate television show as a basis for comments. Communications about quality are good, and the surgeons I know respond appropriately to legitimate concerns.

It’s also not very scientific to generalize about an entire population based on “surgeons I know,” either.

There are many peer-reviewed journal articles that talk about the widespread problem of bad behavior amongst surgeons and physicians.

Not all behave badly, of course.

Bryan – thanks for the tip and sharing the story about the show. My wife DVRs it but I don’t normally watch. I certainly will this week.

[…] teams have the concept of stop the line, where the team gets together to make sure the pipeline clears up for the next features to be […]

[…] teams have the concept of stop the line, where the team gets together to make sure the pipeline clears up for the next features to be […]

[…] happens is an employee “pulls the andon cord” to point out the problem. Management thanks them for this and then works together to resolve […]

In the European style football the coaches asking players to “freeze” in a short moment the play and put the foot on the football. Stop, regroup, rethink, recreate, reapproach….