Following up on my post about my recent experience with metrics and processes being distorted (and my less-than-perfect Lean coaching efforts), I was thinking back to some first-hand experience I had when I started my career at the GM Livonia Engine Plant circa 1995. It's the most blatant example of someone intentionally distorting data that I've ever seen… but it's totally understandable. I blame the senior leaders, not the front-line supervisor, in this case.

Our engine block line was designed at a throughput goal of 92 blocks per hour. We could machine 92 blocks in an hour if everything ran perfectly, but it was rare and extremely unlikely to ever happen… running at that 100% pace for an entire hour.

Our plant superintendent, Bob (he was the #2 guy in the plant), decided that 60 pieces per hour was an acceptable number (partly based on productivity benchmark numbers that were attributed to Toyota). If you produced anything below 60 blocks in an hour, you'd have to explain why.

Now, Bob wasn't really the listening, problem-solving type. He managed by fear, yelling, and intimidation. There was more yelling involved than listening or problem-solving, yet alone any coaching.

Hear Mark read this post — subscribe to Lean Blog Audio

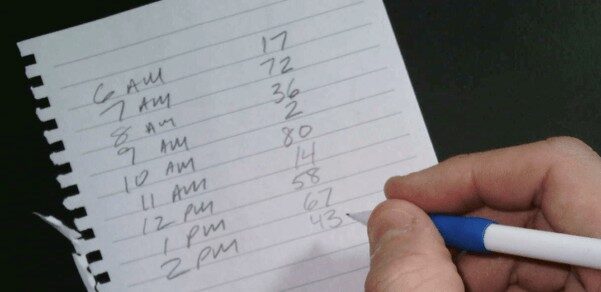

Anyway, at the end of the engine block line was a mechanical counter that recorded the hourly production counts. The UAW workers who unloaded blocks dutifully recorded the number every hour on a piece of paper.

The numbers might have typically look like this as they were written down:

That's an average of 48.6 pieces per hour. Not quite up to Bob's standards, although here we exceeded the goal in three hours and came somewhat close to 92 in one hour.

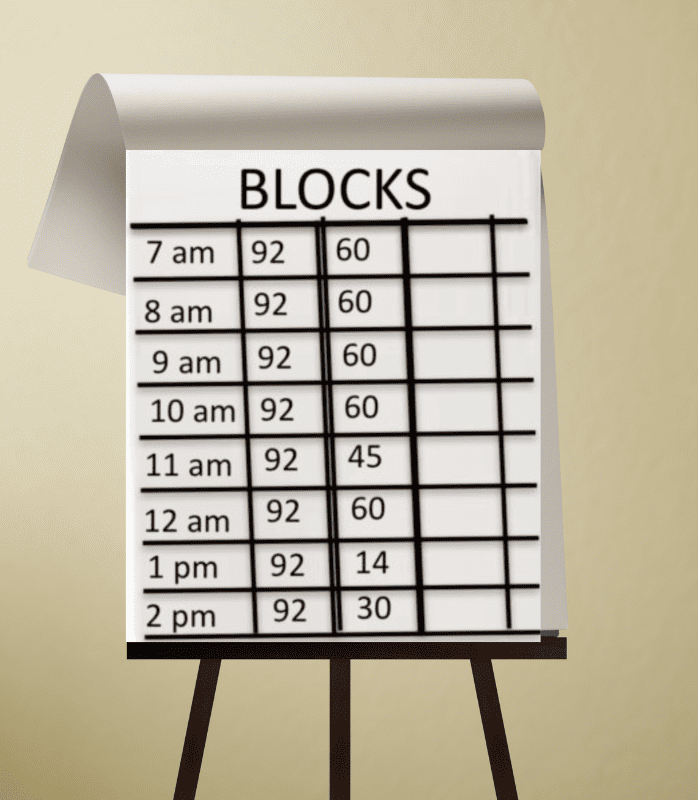

At the end of each day, before our “4 o'clock meeting” where the plant salaried staff took its daily verbal beating from Bob, Scott, the production supervisor (the technical title of “Team Coordinator” didn't quite fit) would pick up the counts and do a little daily editing.

Scott would take the numbers and turn them into something that looked like this, I kid thee not:

That's still an average of 48.6 per hour. But it's much more consistent. Too much so. Unnaturally so. Unbelievably so.

Bad ole' Bob never questioned these numbers. I know it's hard to believe that he would believe those numbers, but when reviewing multiple departments at that daily verbal abuse meeting, Scott's fudgery helped avoid too much attention that a really bad hour would have brought upon him. Rather than asking, “Why don't we have more hours with 86 blocks?” the upper limit of expectations was set too low, at 60.

I asked Scott once why he fudged the numbers each day, and his answer was simple (image the clipped Michigan accent of a chain smoker):

“Bob wants 60 an hour, he gets 60 an hour.”

Other departments got more than their share of the daily beatings. I had a bet with a co-worker each day if Bob would say the word “pathetic” or “miserable” first in his misguided attempts at “motivating” everybody. Bob always had the same pronouncement for our problems: we weren't trying hard enough. And apparently, more yelling from Bob was what we needed to motivate us. But that never worked.

“Not trying hard enough” fell into two categories: 1) urgency and 2) intensity. We didn't have a sense of urgency. We didn't have the proper intensity. Like a shorter approximation of Mike Ditka (with a signature bad toupee rather than a signature mustache), Bob would yell and scream and spit would fly. Sometimes we got “we need urgent intensity” or “we need intense urgency” if things were really bad. All of the yelling and screaming, all of the fear, all of the fudging of the numbers got in the way of true process improvement and true problem-solving.

Obviously, situations like this are part of the reason our plant manager eventually got moved out of the way (promoted and put out to pasture at headquarters) for a new, NUMMI-trained plant manager. That started our road to recovery as a plant. It was never a worker problem; it was a management problem. That's an important lesson of Lean — what's required is a change in management practices and management philosophy.

I'll leave it for another post to talk about that “4 o'clock meeting” and what its goals were supposed to be. The meeting was designed by some internal Lean consultants we had but was co-opted by non-Lean management mindsets. Why weren't the lean consultants being listened to? Again, I'll save that for another post.

What do you think? Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Or please share the post with your thoughts on LinkedIn – and follow me or connect with me there.

Did you like this post? Make sure you don't miss a post or podcast — Subscribe to get notified about posts via email daily or weekly.

Check out my latest book, The Mistakes That Make Us: Cultivating a Culture of Learning and Innovation:

[…] production superintendent was fooled by perpetually faked data. I wrote about it 2007 in “GM Got Gamed.” The superintendent never went to the gemba in a meaningful way, he never saw the […]

Some managers do not get the concept of variability in a process. This example is similar to one I experienced in a hospital. During a meeting of the board, a consulting heart surgeon was presenting data on AMI occurrence. The data showed a normal variation over several months, with an aggregate trend downward. Several members of the board, including the CEO, COO, and the hospital’s process expert voiced concerns that one month’s values were above the average then went down in the following month. This pattern repeated itself, and the individuals wanted to know why all the months did not show a value below the average. The surgeon was well versed in the principles of statistical process control, and he attempted to explain as did I. Alas, to no avail..

Carl – thanks for sharing that story. It certainly illustrates the need for leaders to understand variation. That’s why I always recommend Dr. Don Wheeler’s book “Understanding Variation.”

There’s so much time wasted trying to explain every up and down in a chart when it’s common cause variation or noise in the system. This really interferes with real improvement…

as a manufacturing engineer who started out on a GM engine plant I know the situation. unfortunately it is common in most businesses. I found that an MBA grad seems to have the worst grasp of reality in production.

I agree with you on all counts, Denis. This is a problem today, in the year 2015, in healthcare. People get pressured into making the numbers look good. This happens all throughout healthcare, but I think last year’s VA waiting times scandal illustrates the situation perfectly. You want it to look like vets are only waiting two weeks for an appointment? OK, I’ll make the data look like that… even if that’s not reality.

See here:

https://www.leanblog.org/2014/05/the-real-va-scandal-is-the-long-waiting-times-bad-management-not-gaming-by-bad-apples/

I would go further to suggest that chasing metrics, in general, regardless of the metrics is the wrong methodology entirely. Chase warranty costs, for example, and you succeed in doing one thing – annoying your customer. Chase top line, and you will sacrifice bottom line. Chase on-time, and you also sacrifice bottom line.

This metrics approach takes hold in large corporations especially because, when a firm gets to a certain size, it is literally impossible for senior managers to do anything except manage metrics. Further, this metrics approach is demoralizing because all the senior managers do is beat you up, and there’s ALWAYS a metric that slips.

The only real approach is to develop a continuous improvement attitude and push rocks out of the way of your production…all day long. Then the metrics will follow as the business gets better.

Just my opinion, having been in manufacturing management for twenty years this years (and I have yet to see it “done right” by the way)

I agree with you, Brian. I think the “Balanced Scorecard” type approach to metrics (keeping 4 or 5 key areas in balance) can help, but not everything is easily measurable (such as how well your product fits customer needs, customer satisfaction, etc.). There are measures, yes, but they’re flawed in some way, so judgment and long-term thinking matters too. Thanks for commenting!

[…] union for the company’s problems. I blamed leadership (or a lack thereof, as I wrote about here and […]

[…] The pressure to “make the numbers” isn’t just a healthcare problem. I saw the same thing in manufacturing, including this story from my GM days. […]

[…] thought everybody needed to develop more of a “sense of urgency” (which is a phrase I used to hear at GM 20 years ago… a phrase and slogan that never really […]

[…] and control culture — and everybody suffered: customers, employees, shareholders. But, some managers got to yell and scream at others, acting like the tough guy. But, employees (including me) laughed at them behind their backs. […]

[…] GM Got Gamed (Or, How to Fudge Your Production Numbers) […]