See the transcript later in this post.

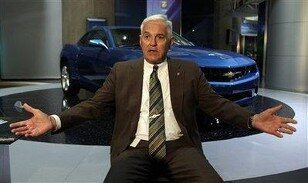

My guest for Podcast #126 is Bob Lutz, author of the book Car Guys vs. Bean Counters: The Battle for the Soul of American Business. Retiring in late 2010 as vice chairman of General Motors, he currently runs Bob Lutz Communications. During his 47-year career in the auto industry, he worked for GM, Ford, BMW, and Chrysler and he's a legend in Detroit, where I grew up.

In this podcast, we discuss his new book, his thoughts on designing products that create value and excitement for customers, as well as some of his thoughts on leadership.

Bob's a “car guy” and a designer through and through, so what he says isn't always classic “lean thinking,” but it's interesting and thought-provoking. What's a “blanderizer”? You'll have to listen (or read) to find out.

I hope you'll take a listen and/or read the transcript below. Be sure to share your thoughts and reactions by posting a comment on this post. I have my own thoughts and reactions, which I've added as comments to the transcript – notated by [MG1].

As I wrote about in my preview post, Lutz says he is a fan of “autocratic” leadership, saying that the pendulum had swung too far during the “total quality” era toward too much slow consensus building and too much employee participation. In talking with him, much of what he's complaining about isn't what we'd recognize as Lean or Toyota thinking, but it's perhaps a reaction to the way the “Detroit Three” were using these TQM ideas in dysfunctional or extreme ways. He says we need more autocratic leadership, yet he doesn't think he's an autocratic leader, nor would he want to work for one. Interesting stuff.

For a link to this episode, refer people to www.leanblog.org/126.

For earlier episodes, visit the main Podcast page, which includes information on how to subscribe via RSS or via Apple Podcasts.

If you have feedback on the podcast, or any questions for me or my guests, you can email me at leanpodcast@gmail.com or you can call and leave a voicemail by calling the “Lean Line” at (817) 372-5682 or contact me via Skype id “mgraban”. Please give your location and your first name. Any comments (email or voicemail) might be used in follow ups to the podcast.

Transcript [with Mark's comments]:

Mark Graban: Well, our guest again is Bob Lutz, talking about his new book, “Car Guys vs. Bean Counters.” [2:01] Now, Mr. Lutz, you're a car guy extraordinaire. You've been critical of MBA educational mindsets, so I was wondering if you can describe, what is a bean counter, and why is it that it's not just accountants who can become bean counters, unfortunately?

Bob Lutz: [2:18] Bean counters is not so much a profession in that I know many finance people who are extremely skilled at finding value in the product and pushing that. But the bean counter mindset is a person who can be in any field – sometimes you encounter them in engineering – who absolutely want to quantify everything[MG1] , want to go for cost minimization on everything[MG2], and who understand cost and cost reduction. [2:52] But they do not understand value creation [MG3] in terms of making a superior product or offering a superior product or superior service that's going to delight customers, create good word of mouth, and have the customers buying again.

Mark: [3:10] I've heard you talk before that the customer is not always right. Besides relying on your gut and decades of experience, how can people go about determining what's of value, what's going to delight and excite customers?

Bob: [3:23] Well, I think the best way is the way we do it in the car business. We do a full-scale model of the future car and we test it with respondents against competition, with all of the cars disguised so they can't tell what brand it is. Because the minute they know what brand it is, they vote by brand instead of by how well they like the car. [3:44] That's another reason why in research techniques the reason I say the customer isn't always right, because what the customer verbalizes as his or her desires are often the socially responsible or the socially acceptable reasons, but they don't get at the hidden purchase motivation.

[4:06] For instance, if you were to ask men, “How important to you is it to have a $10,000 wrist watch?” Most guys will say, “That's not important at all. Wrist watches are here to tell time, a $30 Timex will do just as well.” And you believe that at your peril.

[4:28] The same is true with cars. If you ask people this tired old question, “When it comes to cars, what's important to you? Is it styling, safety, convenience, etc.?” The average respondent will say, “Styling is not important. Performance is not important. I want a solid, reliable car with plenty of room for my family.”

[4:54] In other words, they're always giving you rational reasons. But humans aren't rational beings. When inside themselves there is this boiling pot of emotion and lust, inevitably, they'll go out and buy a good-looking car. That's why I say you have to understand the hidden motivations of customers or find research techniques to get at those.[MG4]

Mark: [5:18] Now, I saw you give a talk at Harvard Business School in the late '90s. I was a MIT student at the time. You were probably talking to a lot of budding bean counters, and I think I recall you talking about a goal in design being to create products that people really love or really hate. That it was OK to have products that were hated by some, instead of…

Bob: [5:40] Here's what happens and this is typical of the bean counter mentality. And I've seen perfectly good automobile proposals wrecked dozens of times by trying to get rid of dis-satisfiers. In other words, they will try to get rid of, based on research, they'll try to get rid of every controversial element on the car, and this is what I call putting it through the “blanderizer[MG5] .” [6:11] At the end of the day, the car comes out totally neutral. It has no character, doesn't displease anybody, but also, doesn't please anybody. So you're far better off, since human beings are wildly diverse in their tastes and desires, and whether they're conservative, stylistically conservative or stylistically progressive, you have to do a very bold design that has an emotional impact.

[6:40] And then, if you get a situation where 50 percent of people absolutely love it and 50 percent hate it, that's ideal. That's far better than 80 percent of people saying, “Yeah, it's OK.” Because if 80 percent say it's OK, it means it's everybody's second choice. Nowadays, nobody buys second choices anymore. They don't have to.

Mark: [7:03] Maybe if we can shift a little bit from design to management principles, one question that I guess I would ask about the auto industry first. Where would the Big Three be today if they had been run more by the car guys? Do you think there's any hope of that balance shifting in the future toward the car guys?

Bob: [7:27] Well, I think it has shifted toward the car guys at all three of the Detroit companies, and it's especially manifest at General Motors and Chrysler if you look at the cars they're putting out. I mean, these cars are just done exquisitely well. They're well designed. They have beautiful, rich interiors, and so forth. [7:44] Manufacturing was never really short-changed that much, because manufacturing is a rational activity. You put in a certain amount of capital and labor. You build a certain plant, etc. You can calculate your cost of that plant down to the labor minute and you've got a full manufacturing cost of every unit made in that plant.

[8:11] So manufacturing is a rational activity. It contains very little emotion [MG6] and therefore, the bean counter mentality in optimizing manufacturing actually works pretty well. I would say American manufacturing, certainly in the automobile business, today, I will put up against anybody in the world — German, Korean, Japanese.

[8:37] All the Big Three plants today[MG7] are wonderful examples of lean manufacturing, just-in-time, hands-on corps, etc., that no in-process inventory, error-proofing on the line, etc. I mean, everything is there. The only reason why any company would still have a manufacturing advantage over the United States would be purely do to exchange rates or labor costs.

Mark: [9:05] Now, shifting to the management topics here, I saw an interview you did with the “Wall Street Journal” where you were critical of what you called the total quality approach to management, and you were advocating for autocratic CEOs. Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

Bob: [9:22] Well, I did have a problem with the TQM consultants in – what was it? – the '90s, where they descended on all companies. We went through these elaborate off-site deals [MG8] that lasted five days and everybody held hands. That's when all the posters went up saying, “Listen to everyone with respect. There is no such thing as a bad idea[MG9] .” [9:48] I mean, that is unmitigated hogwash. Of course, there's such a thing as a bad idea.

[9:54] The idea that it should be a democratic, pleasant, wonderful chaos in a company, where everybody discusses endlessly and nobody ever says, “OK, look. We've discussed this enough. We've got a decision to make, and we're going to go with B and not A.”[MG10]

[10:19] Well, then all of the people who were in favor of A are disappointed, but at least you've got a decision. Speed is of the essence. It's better to make a marginal decision on time than to make a perfect decision too late. I've just seen too much of vacillation, endless discussion. “Well, we didn't come to agreement on that. Let's meet again next week and discuss it again.”

[10:48] Of course, nobody ever changes their mind, and if the boss doesn't step in and say, “We have discussed this enough. We've got to make a decision, and here's how we're going to go.” I think the United States industrially went too far in what I call participative decision-making, where the boss is afraid to step in and make the decision. He's hoping the team will sort it out among themselves.[MG11]

[11:15] I'll tell you, that doesn't work. It's about like a family with nine kids all milling around the house, and the parents say, “They'll sort it out. They'll probably set the table at some point and cook the food.” Unless mom and dad set the direction[MG12] , it's going to be chaos.

[11:34] I don't like working for autocratic bosses, and I don't think I was one. I was when I had to be, but I was reluctant to step in and say, “Do it my way,” because it's not the way you like to lead. But if you look at companies that are run by super autocrats, like Volkswagen under Winterkorn and before Winterkorn, Ferdinand Piech, where it was literally, “You do as I say. My way or the highway.”

[12:01] He would not only tell them how to do it, he would tell them what to do – a totally autocratic system where everybody lived in fear[MG13] . I would hate to work for a company like that, and I know that a fear-driven environment is not a pleasant one[MG14] , but Volkswagen Audi today is the most successful car company in the world. They're on the cusp of becoming the world's largest automobile company, run by total autocrats[MG15] .

Mark: [12:32] My experience, when I worked at General Motors in the mid '90s, we had a plant manager who was one of the first GM people sent to work at NUMMI out in California. I think that leadership style is not completely autocratic. It's certainly not completely participative. I was wondering if you could share some thoughts on lessons learned from GM's partnership with Toyota at NUMMI in terms of finding that balance in the management style.

Bob: [13:03] I think, in general, the study of Japanese management techniques or Japanese leadership techniques as observed during the '70s and '80s really helped American leadership a lot, because we didn't have a leadership style. [13:21] The leadership style we had in the United States was often too autocratic[MG16] . Or bosses being so proud of having achieved their position, and since they had been mistreated when they were underlings, they said, “Well now that I'm on top of the heap, I'm going to treat the people the way I was treated.” [MG17] Make them jump. Demean people; tear them down in meetings and so forth. That was all bad stuff.

[13:45] Very valuable lessons were learned from NUMMI. Chrysler got the same lessons from Mitsubishi, and Ford from Mazda. I think what we now have is a successful blend of the good parts of the Japanese consensus system and the participative system. I think we're learning to re-achieve the balance[MG18] , because I think we went way too far the other way. It was the usual pendulum reaction.

[14:19] I think we're coming back to the middle now, where people are empowered, but they understand who the boss is. They understand they're under time pressure. They understand they've got to come to a decision, and if they don't, the boss is going to make it for them. That is certainly the way GM is being run right now, and I think it's the right balance.[MG19]

Mark: [14:41] One other question on balance: in the book, I thought it was interesting where you talked about your last stint at GM, trying to find in your own leadership style the balance between teaching and telling. Can you share a thought on that?

Bob: [14:56] I like to teach rather than tell because telling is, I think, the lazy man's way[MG20] . You just say, “Look, I don't have time to explain it to you. Do it this way.” I think that way, people will accept it, but they'll accept it grudgingly. There's a certain amount of resentment. [15:15] But if you say, “Look, based on my experience and on similar situations I viewed in the past, if we did your way, here's what I see happening. I've not only observed this once, I've observed it three times in my career. That's why I'm reluctant to say yes to your proposal, because my experience tells me it doesn't work.” [MG21] You actually cite the examples.

[15:40] Well, that takes a little longer, but hopefully the individual has learned a little something, and at least he or she understands why you decided against their proposal. So if the time is available — and let's face it; it usually is — I always like to explain. The more unpopular is the decision, the more I go out of my way to try to explain it.[MG22]

Mark: [16:07] Mr. Lutz, maybe just one last question on the topic of “Car Guys vs. Bean Counters.” In the book you talk about this a little bit. If you can, share some thoughts on the idea of the car guy being applicable in other industries. You used Steve Jobs as a positive example of this. Would you think, for example, should hospitals run by doctors (readers, see this blog post) — do you think they are the equivalent?

Bob: [16:27] See, you could argue that General Motors and Ford right now are two successfully run car companies – and even Chrysler – that are not run by what I would call car fanatics or product people. It's not so much that they have to be subject experts in the product or service that they're putting out. It's that they have to be passionately committed to the excellence of the product or service that they are producing. [15:10] I'm not sure it would work to have hospitals run by doctors because doctors sometimes are notoriously poor administrators. So I see nothing wrong with having professional administration running a hospital, provided that that hospital administrator is passionate about listening to the doctors who serve on the staff and is passionately committed to providing the best healthcare experience for the hospital customers that is possible[MG23] .

[17:28] As opposed to, as many do, focusing all their time on “Where can we cut costs? Where can we reduce receptionists? Whose phone lines can we take away? Can we go from five ambulances to four?” Spending all their time on cost optimization and hoping that they can somehow get away with it without the customers noticing.[MG24]

[17:53] It's more a mentality thing than it is being a subject expert.

Mark: [17:56] Thank you very much. Again, our guest has been Bob Lutz. Thanks for sharing your reflections and talking about your new book, “Car Guys vs. Bean Counters.” I'm really enjoying it so far, and I hope others will go out and check it out.

Bob: [18:12] Great. It shouldn't take you too long to read it. It's an easy read. You get through it in about three hours.

Mark: [18:14] Yeah, I got through a good chunk of it last night, and it's really a pleasure to be able to talk to you today.

Bob: [18:20] OK, thanks very much. Good talking to you, too.

[MG1]This makes me think of Dr. Deming's lesson that some of the most important things in business are actually not measurable.

[MG2]There's a big difference between cost-cutting thinking and lean thinking that focuses on waste and customer value.

[MG3]Here, he sounds like a lean thinker.

[MG4]This is a good reason to involve patients in the hospital design process, being a part of mockups and other “lean design” approaches rather than just doing a focus group.

[MG5]I love this term!

[MG6]This seems like a comment from a non-manufacturing guy. Factories are technical, social, and political environments, so I think he overestimates how rational (and therefore easy?) factories are.

[MG7]My experience in GM was 1995 to 1997 and we were nowhere near as good as Toyota. Today, harder for me to say.

[MG8]Yeah, probably a waste of time.

[MG9]You can both listen to respect and yet still have constructive and authentic discussions with employees without humoring people. If someone has a “bad idea,” in a lean environment a leader has to probe and challenge and ask questions to coach and educate and drive to a better idea.

[MG10]Again, this doesn't sound like Lean to talk about things forever and not make a decision.

[MG11]This is why John Shook always emphasizes that lean leadership is NOT hands off delegation. There's still a role for the boss.

[MG12]Lean leaders set direction (although it's not quite a parent/child relationship by any means).

[MG13]This is bad.

[MG14]I agree with Bob here.

[MG15]So is VW doomed to failure then? Or does that style work somehow??

[MG16]And often still is!

[MG17]I sensed a lot of that when I worked for GM.

[MG18]Balance is good.

[MG19]I would tend to agree with him.

[MG20]Yes, completely agree.

[MG21]That's the language of a coach and a teacher. I've learned in lean management that if you have to be directive, then you have an obligation to explain why.

[MG22]Great advice.

[MG23]Much as my blog readers said, MDs or MBAs could have this attitude.

[MG24]There are plenty of bean counters in healthcare!

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-238x178.jpg)

![When Was the Last Time a Leader Around You Admitted They Were Wrong? [Poll]](https://www.leanblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Lean-Blog-Post-Cover-Image-2025-07-01T212509.843-100x75.jpg)

From a Facebook friend:

“Listened to it today. At first his statement about needing more autocratic leadership seemed off-base, but as I listened he made a lot more sense. No need for much “kumbaya.” Actually, I thought what he said fit well with the lean idea of thorough, deliberate, careful planning, then implementing rapidly. Good interview, Mark, and nice to have a little break from healthcare with a “car guy.””

Fine interview, very interesting, thoughtul guy — thanks Mark.

Here are some initial reflections.

Mr. Lutz has terrific Design insights, as you might expect. “Blanderizer” is a great term! He infers the importance of understanding “Delightful” quality, as well as, Prescribed & Expected quality. (Check out chapter 8 of The Remedy http://www.amazon.com/Remedy-Bringing-Thinking-Transform-Organization/dp/0470556854/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1313174134&sr=8-1for more).

Interesting that Mr. Lutz invokes the Leader = Sensei mental model. Not what you’d expect based on what you hear about him.

His ambivalence toward autocratic management is also interesting. He’d hate to work in such an organization, but then again…seems he believes they’re effective.

Those are some off the cuff thoughts. More coming.

Regards,

Pascal

Thanks, Pascal. I had very similar reflections. I was pretty turned off when I first read that he was advocating for “autocratic CEOs,” but after seeing his WSJ video interview and then talking to him here, I realized it’s a much more nuanced approach than the WSJ headline writers would lead you to believe.

I really loved the idea, going back to the first time I saw him speak, that you don’t want to design for the average product that will be “meh” to the bulk of your audience. This was before Lutz’s time and he had to defend it somewhat, but some might argue the dreaded Ponitac Aztek was that sort of product. Most people thought it was hideous, but many people really loved it actually.

There are comparisons made to the new Nissan Murano Crosscabriolet (Pic).

Most find a convertible crossover vehicle to be really bulky and ugly, but they don’t need everybody to buy it.

Looking forward to hearing more of your thoughts.

Mr. Lutz acknowledges the positive influence of Japanese management techniques. Seems he’s learned from Toyota & believes its methods have helped transform Ford, GM and Chrysler.

As Mark suggests, Lean management isn’t about wishy-washy consensus — it’s about results. Involving people doesn’t mean abrogating leadership. (Not sure Mr. Lutz got that part)

Mr. Lutz’s vigour and thoughtfulness come through. Seems the media may have caracatured his ideas. I was expecting an old fossil…

I guess I would wonder how much better Volkswagen could be if they had ways to use more input and ownership from their employees.

[…] to see a woman as CEO, but I’m more excited that Barra is an engineer. You might be recall my podcast interview with former GM product chief Bob Lutz, who talked about the importance of “car guys” (of either gender) over “bean […]