Last week, I taught a pilot session of a new class on Kaizen and continuous improvement that I taught for visitors to the ThedaCare Center for Healthcare Value. Unlike other workshops that have assumed people are starting from scratch, this was designed around exercises, simulations, discussions, and two “gemba visits” to see daily team huddles (one at ThedaCare and one within the Center).

I used an exercise that has worked well in the past to demonstrate how Kaizen is done – solicit, discuss, and test ideas.

Some photos from different steps in the exercise:

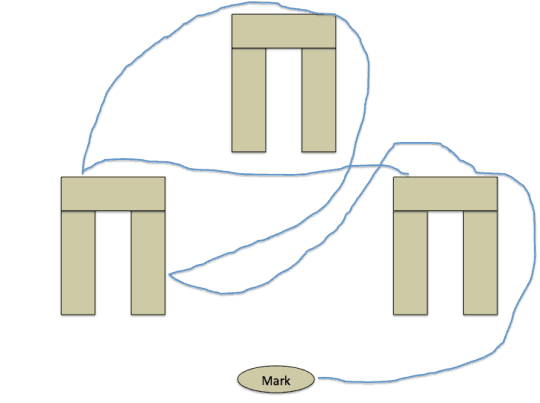

The initial process flow and layout is intentionally bad. The five stations are far from each other, which necessitates batching. Here is the layout and the initial “spaghetti diagram” showing the flow (or lack thereof) of the envelopes being stuffed.

After the first round of envelope stuffing, I led a team huddle for the participants, trying to demonstrate how the Kaizen Board is used and what behaviors we try to exhibit while doing this.

The team identified problems and came up with ideas for improvement – either on their own or because I asked them and prompted them to think about it. “What do you think we could do?” is a key question to use in the workplace. If staff have been dependent on the manager having all of the answers, you have to break that habit and help develop people.

They came up with a number of ideas to test, including:

- Moving the five workstations so they were in line with each other and next to each other

- Reducing the batching to single piece flow (now that the layout was better)

- Rearranging some of the stations

They had more ideas, but we chose to just implement a few — focusing on better, not perfect.

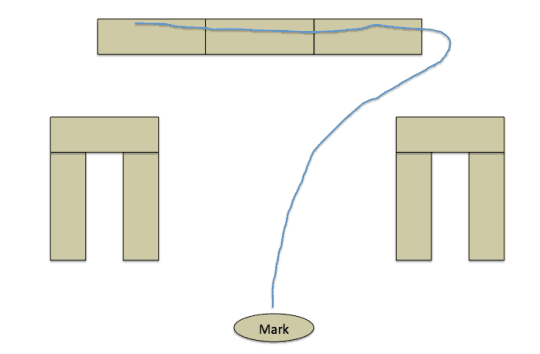

Here is the layout they came up with, and the expected spaghetti diagram:

I've seen teams do this simulation and Kaizen process probably 25 times.

I could have jumped in with a suggestion, but I held myself back. My idea (or the problem I saw) wasn't a matter of life or death. If it were that critical, I would have had an obligation to speak up.

Here, I was wondering why they didn't point the long table toward me, putting the last operation next to me (the customer).

They ran the second round of the exercise. The time required to deliver five envelopes, as usual, was reduced by about 65% — through a better layout and less batching.

I asked them what waste they saw this time or what Kaizen opportunities there were.

Sure, enough, one of the participants realized what they should have done and, had we done a third round, they would have rotated that long table 90 degrees.

Had I spoken up and made that suggestion before round 2, they would have had their improvement a little sooner.

But, would I have shortcut their own learning, development, and confidence?

When they brought up the idea, I didn't say, “Why didn't you notice that earlier???”

I did point out, for the sake of illustrating my thinking as a facilitator, that I intentionally hadn't spoken up. I didn't give them the answer. I trusted they would figure it out eventually.

I'm paraphrasing John Shook from the Lean Enterprise Institute, who said something to the effect of:

“When you give an employee an answer, you rob them of the opportunity to figure it out themselves and the opportunity to grow and develop.”

I don't think people get better at problem solving and Kaizen by being given answers. They get better by thinking, experimenting, learning, and adjusting. It's the PDSA cycle in action.

Can you think of situations, in the workplace, where you gave somebody an answer and regretted it? Have you gotten better at not giving people answers? Have you tried to coach others and encourage them to let people figure things out on their own?

Where do you strike the balance between “improve now” and “develop people?”

Please scroll down (or click) to post a comment. Connect with me on LinkedIn.

Let’s work together to build a culture of continuous improvement and psychological safety. If you're a leader looking to create lasting change—not just projects—I help organizations:

- Engage people at all levels in sustainable improvement

- Shift from fear of mistakes to learning from them

- Apply Lean thinking in practical, people-centered ways

Interested in coaching or a keynote talk? Let’s start a conversation.

[…] Kaizen Coaching: Don’t Give People Answers, Let Them Learn […]

I regret every single time I’ve told someone the answer. It’s not only that some people may think that a person who always has an answer is a know-it-all or ‘needs attention’; it’s that giving people the answer teaches them that they should defer to the expert. It creates dependency and undermines accountability. This was such a difficult lesson for me to learn that I’ve put it into my ‘elevator speech’:

“I create environments where people with differing (and often conflicting) agendas can come together and decide how to overcome the barriers that stand in the way of best practices. It’s not about telling people what they should do; it’s about allowing them to discover that working with people in other disciplines is a powerful way to improve performance.

Even if you know where the problem begins and have a perfect solution in hand, humans only engage, take ownership and become accountable when they participate in finding problems, testing solutions and deciding how to measure success. Once people have a personal experience of collaborating with others and achieving success, they will become the organization’s strongest advocates for improvement programs.”

You created an environment Mark, and then stood back and bit your tongue. They learned how to work with other people on an improvement issue without running to the consultant. A physical exercise will be remembered more strongly than a class presentation. The strongest memories of all will be when they realize that after working with people from other areas, their team did something that actually improved patients’ lives.

That’s awesome, Denise. Thanks so much for sharing that with us and, more importantly, for having that mindset and approach. Well said.

Letting your subordinate to figure out the solution is a crucial step in developing them. However, it is also important to coach them and assist them in the direction they need to follow. My experience working with superior that only interested in giving the task without any coaching only leads to frustration and less motivation in finding the solution. In the end, I think both parties need to communicate for better learning environment.

I agree that the manager or consultant should certainly coach and be involved. Asking questions can be more effective than just telling.

In this exercise, I could have asked the team “is there a way to reduce the distance to the customer?” or “do you see any other ways to reduce the time it takes to deliver a completed envelope to the customer?”